Sound effects in song production could eventually lead to misleading identifications.

When we started to develop our audio fingerprinting technology, we made sure it worked with every sound we recorded but we still had a way ahead to delve into its nuts and bolts and overcome some of the oddities of our industry. This leads us on to the fascinating world of sound effects.

Some weeks ago we wrote about how an audio fingerprinting system works. The conclusion was that, if well designed, it’ll be able to match an audio with its fingerprinted representation. If they proceed from the same sound recording they will invariably match and you’ll identify the song you are listening to.

Fingerprinting is sort of like a natural law, it works without fail and regardless of the circumstances, and as such it might feel a bit too strict and rather stringent. Take the law of symmetry for example and the unforgiving outcome when staring in the mirror. Or there’s the severity of gravity when you’re Keith Richards at 62 and decide to climb a coconut tree in Fiji. It’s more than likely you’ll be pulled towards the ground.

“Symmetry and gravity work so rigidly, we can be brutally reminded when we take them for granted. The same applies to audio fingerprinting, it could become a smart-ass solution if you’re not sure how far you can trust it.”

Symmetry and gravity work so rigidly, we can be brutally reminded when we take them for granted. The same applies to audio fingerprinting, it could become a smart-ass solution if you’re not sure how far you can trust it. More specifically if it’s well programmed, the matches are undeniable but there are certain circumstances where this isn’t useful for the interests of our industry.

For example, we have the audio fingerprint of Nick Cave’s Cocks’n Asses, which means we can recognise the song wherever we monitor it. The same goes for Barry Adamson’s The Vibes Ain’t Nothin’ But The Vibes.

Towards the end of Cocks’n Asses, at 5:28, you can hear people cheering and a fade-out effect. If you then listen to Barry Adamson’s The Vibes Ain’t Nothin But Vibes, you don’t need to have an inbuilt fingerprint to notice the song includes the very same exact sound at 4:35.

The same happens if you listen to Rhapsody of Fire’s Heroes of the Waterfalls Kingdom followed by Jorn’s Tungur Knivur.-, you’ll realise both songs start in a windy and stormy night.

In short, the use of sound effects in song production could eventually lead to misleading identifications.

Stop children, what’s that sound?

In general, sound effects go unnoticed by general audiences and they aren’t topical in the music industry. Nevertheless, if you pause for a second to acknowledge them, they’re more common than we think in everyday lives. Plus, the people creating them are artists themselves. Check out this video:

Some online libraries contain up to 700,000 different sound effects. You can find the perfect car horn, stormy nights, people cheering or even cheese grating sounds. These are mostly used for music production and audiovisual companies, but some commercial songs include sound effects as well – especially in hip-hop music.

All in all, they’re a useful resource and they compliment a vast amount of music and audiovisual content. Our problem arises when we analyse an excerpt of a song which includes the same sound effect as a completely different song. Or similarly, when we identify a sound effect while monitoring a movie on TV and it matches as well with a different song containing the exact same effect.

Our technology detects this short sound effect – embedded in many different sound recordings – and matches it with a particular song. There are chances the short audio snippet confuses the algorithm and a spurious mismatch sneaks in the report. Fingerprintingly talking, the match is correct because the technology is doing its job – pairing identical sounds – but the result might not be the needed one for the industry.

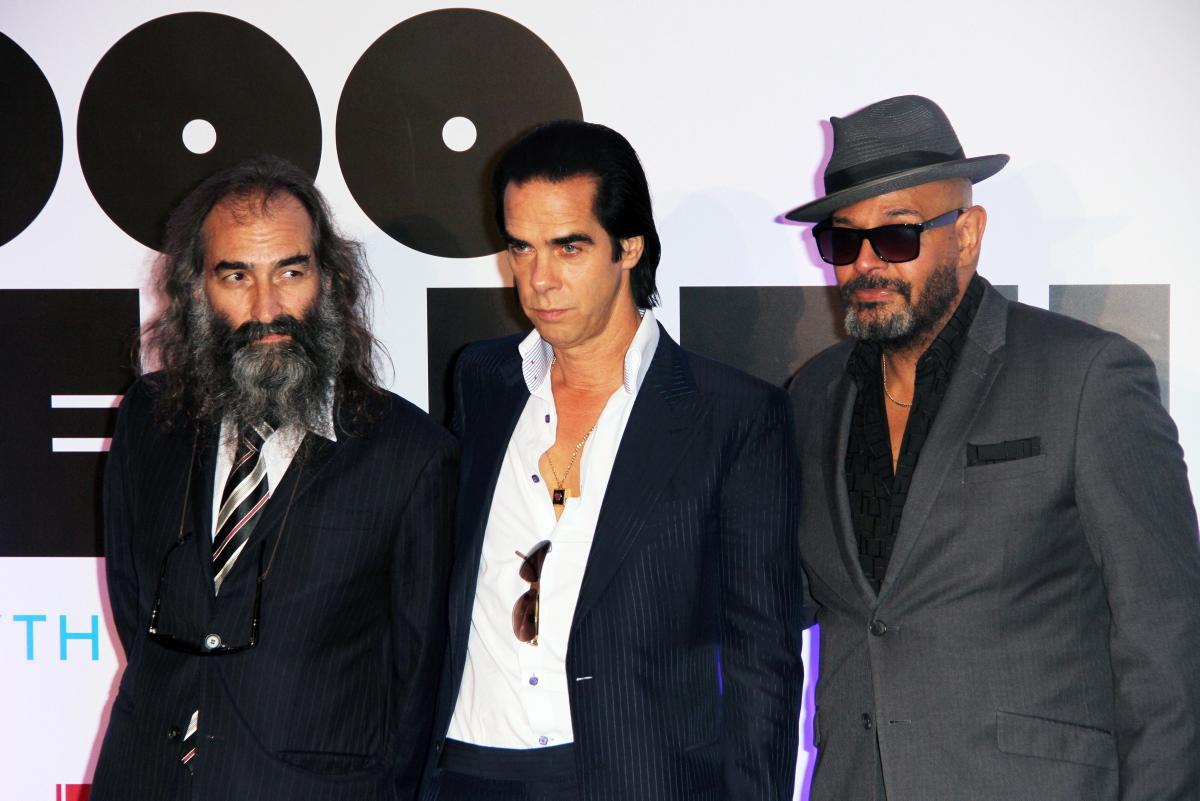

Nick Cave (centre) and Barry Adamson (right) shared 2 years in The Bad Seeds, but also some of their song’s sound effects since then on. Picture by Gagarin Magazine. Main picture by Tatacliq.

Every royalty in its right place

To make sure that Nick Cave and Barry Adamson perceive their due royalties but not each other’s, we walked a long path towards the solution that fits the needs of the industry. We first had to understand that an ugly face will always look ugly in the mirror, as well as that Earth gravity always attracts us to its centre – audio fingerprinting works regardless what you’re looking for.

To exclude sound effects from the audio was the first idea, but it isn’t a valid option – if you’re only focusing on audio there’s no way to tell the difference between a sound effect or an original sound produced ‘ad hoc’ for a song.

Furthermore, sound effects normally appear mixed up with correct and extremely short identifications. The next proposed solution was to match excerpts longer than two seconds – the minimum required duration for an identification – but that would end up skipping many correct matches.

To add fuel to the fire: sound effects producers don’t generate any kind of royalties, so they don’t upload their works to our system and we can’t exclude them from music reports. The options to solve this involve collaborating with foley artists and enabling everyone to upload their sound creations to the system, then we could create a Sound FX category and exclude them from the commercial matches. However, this solution would be timely and potentially over-engineered – a forbidden art at BMAT

“Summing up, we’re developing a collection of sound effects so that they’re excluded from the matching process.”

We’ve put our heads together and found a solution to detect false positives as a matter of triangulation. When we notice that a recording matches with many different sound recordings with different metadata, then we understand that the match is incorrect, i.e. the recording has nothing to do with the match in terms of metadata but only perceptually. We check why this happens and, in case that sound effects are involved, we send these effects to a particular audio collection which is banned from the identifications. This means that whenever they’re played, the audios from this collection will be identified, but the system won’t match them to any song.

Summing up, we’re developing a collection of sound effects so that they’re excluded from the matching process. It doesn’t make it easier to climb coconut trees in your elderly, nor to receive great feedback from the mirror if you normally don’t. But it does let Nick Cave use cheering voices without giving its royalties away to Barry Adamson or the other way around.

Written by Brais, Head of Comms

Latest articles

November 19, 2025

Inside BMAT DSP Processing: How SIAE turned operational clarity into stronger licences and faster distributions

Some relationships last because they work, others last because they grow. For more than 10 years, we believe the partnership between SIAE and us has done both. Across products and people, w [...]

October 9, 2025

KODA and BMAT Announce Landmark Global Partnership for Music Rights and Royalties Management

BMAT, a global leader in music technology and rights and royalties data, is proud to announce a new partnership with KODA, the collecting society for songwriters, composers and music publis [...]

March 26, 2025

Inside ReSol: An interview with SACEM on rethinking how digital claiming conflicts are resolved

Much like family gatherings, the intricate world of digital music rights is no stranger to conflict. With frequent occurrences like overlapping ownership claims, metadata inaccuracies, lice [...]