In sound engineering and acoustic science, the human voice is considered the most intricate musical instrument, capable of producing a vast array of tones and frequencies that can be precisely analysed and manipulated for both spoken and musical expressions—yours included, whether you can sing or not so much.

The riddle we’re tackling today is whether the evolving use of voice data in AI can be ethically sourced and properly traced.

As with every other element employed in AI, ethical concerns emerge around the extent of manipulation and the privacy implications involved in the advancing use of voice data. The human voice has also become a digital asset that can be used for AI training. This raises important questions like How unique is the human voice? Can it be cloned? Where do we come into play? How does the BMAT AI certification work?

Keep reading to get our insights with a side of musical witty banter to spice things up.

Voice frequency 101

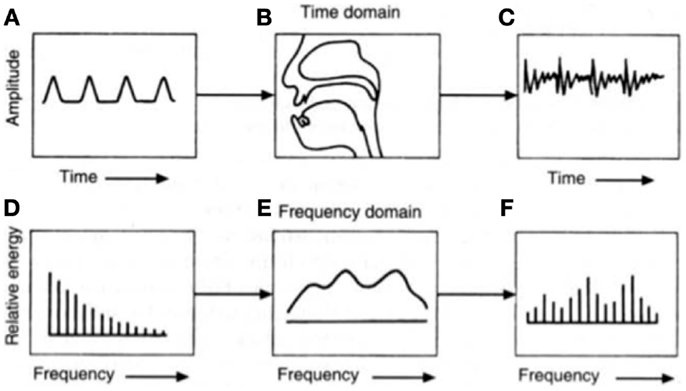

As engineers and notorious music geeks, we must start by laying down some sonic groundwork. Frequencies, measured in Hertz (Hz), represent the number of vibrations a sound wave completes in one second. One kilohertz (kHz) equals 1,000 Hz.

The human voice frequency spectrum exists entirely within the realm of sound waves. Human ears typically pick up frequencies between 20 Hz (a low rumble) and 20,000 Hz (a high-pitched whistle).

While we can perceive this wide range of sounds, the frequencies most crucial for understanding speech lie within a narrower band, typically between 500 Hz and 4,000 Hz. Interestingly, our ears are most sensitive to frequencies between 2,000 Hz and 5,000 Hz, allowing us to detect even the faintest sounds in this range.

Frequencies outside the 500-4,000 Hz range are not as essential for speech comprehension, but they contribute significantly to the overall quality and character of a voice. For instance, vocal fry (low frequencies) and sibilance (high frequencies) add unique texture and timbre to each person’s voice.

Our voices are about as unique as our fingerprints

In fact, each voice has a unique trait shaped by the intricate interplay of anatomy and learned behaviour. Our vocal cords, vocal tract, including the throat, mouth, and nasal cavities, and even the resonating properties of our skulls all contribute to our distinct sound.

The way we articulate and pronounce words adds further personalisation to our voices. This complex combination of factors makes our voices as unique as fingerprints.

Deeper truths than meet the ear

Your voice reveals deeper truths than meet the ear. Besides the spectrum of frequencies that differentiate normative male and female voices, ranging from the lower 100 Hz to the higher 17 kHz, these frequencies also paint an auditory portrait that our brains subconsciously use to imagine a speaker’s appearance or emotions, even before we see them.

Recent research has shown that it could be possible to detect clinical depression from audio-visual recordings, as speech may offer a source of information that bridges subjective and objective aspects in the assessment of mental disorders.

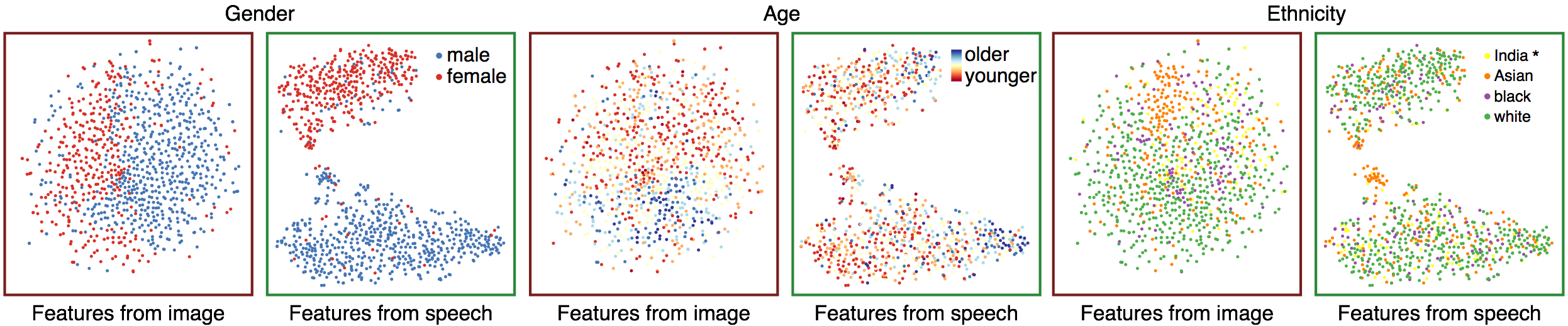

But it gets better. Machines can now infer details like your age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and health conditions. Researchers have also managed to create facial images using just voice data.

The first Talking Heads

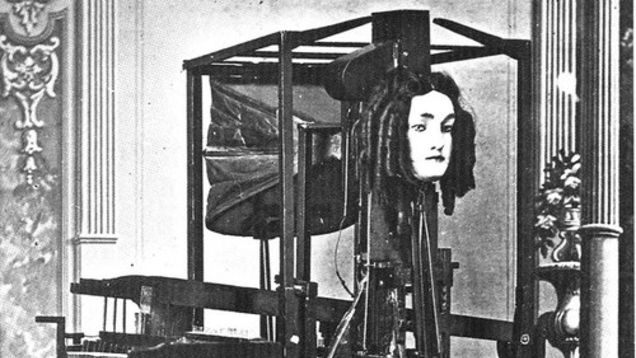

The journey of voice cloning is a tale of innovation, tracing its origins back to the 19th century when early pioneers in speech synthesis embarked on rudimentary attempts to create synthetic speech.

It was 1846 when Joseph Faber invented Euphonia, a mechanical device that attempted to replicate vowel sounds and some consonants in European languages.

Behold the glamorous lady rocking some seriously trendy hair in the picture below.

These endeavours, utilising basic methods like formant synthesis, produced voices that were unmistakably robotic, lacked naturalness, and were even considered creepy by some.

And let’s not forget The Voder—an old-school synthesiser from 1939. Dudley’s Voder was a groundbreaking invention with keys and a foot pedal to control various aspects of sound generation, allowing operators to produce rudimentary speech sounds.

While these marked significant advancements, true voice synthesis technology emerged from the evolution of speech synthesis and text-to-speech (TTS) systems in the mid-20th century. Initially, these systems produced robotic and unnatural speech. Later, concatenative synthesis in the late 20th century utilised recorded human speech segments, leading to more natural-sounding results. Still, limitations persisted due to recording quality and the challenge of accurately cloning specific voices.

Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do

In 1961, a notable event took place at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey. An IBM 7094 mainframe computer, a substantial machine for its time, became the first computer to synthesise a human voice singing a song. The chosen tune was the classic “Daisy Bell,” also known as “Bicycle Built for Two.”

This historic recording was the result of the combined efforts of physicist John L. Kelly Jr., Carol Lockbaum, and computer music pioneer Max Mathews.

This achievement resonated far beyond the scientific community, finding its way into popular culture. Renowned science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, upon witnessing a demonstration of the singing computer, was so inspired that he incorporated it into his 1968 novel and subsequent film, “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Clarke’s memorable HAL 9000 computer, in its final moments of consciousness, poignantly sang “Daisy Bell,” echoing the work of the IBM 7094 and linking this song with the early days of artificial intelligence and computer-generated music.

From 8-bit rattles to Hi-Fi elocution

The surge of neural networks and deep learning in the late 20th and early 21st centuries knocked voice cloning on its head. Computers suddenly mastered mimicking human speech with unprecedented accuracy. This groundbreaking tech owes a nod to early pioneers like Holmes and Shearme, whose “Speech Synthesis by Rule” 1961 paper laid the groundwork for rule-based synthesis, shedding light on the clunky “robotic” voices of yesteryear.

Now let’s zip back to the present. Fast-forward to today, we’re talking about WaveNet, a game-changer from Oord and team in 2016, and the slick end-to-end systems showcased in Sotelo et al.’s 2017 work. These breakthroughs have dialled up the quality and realism of synthesised speech, bringing us closer to voices that sound as human as they come.

The breakthrough in voice synthesis came with the rise of deep learning and neural networks, which analyse extensive speech data to accurately replicate voice patterns. By training on large datasets of audio recordings, these models can generate highly realistic replicas of a person’s voice, capable of delivering text inputs with surprising fidelity. This technology has enabled diverse applications such as personalised voice assistants and entertainment, but it also raises ethical concerns regarding misuse and deception.

Current voice cloning systems use advanced machine learning algorithms and neural networks to mimic the nuances of a person’s voice, including pitch, tone, rhythm, and pronunciation.

Operating in two stages—training and synthesis—the systems learn from a diverse dataset of the target speaker’s audio recordings during training. Once trained, they synthesise new speech by analysing text inputs and producing audio that closely matches the original speaker’s voice characteristics through complex linguistic analysis algorithms.

How is it used in the music industry

Among the many technological advancements emerging in the industry, voice cloning stands out as an influential tool. Leveraging the power of AI, voice cloning could be a tool for musicians, producers, and creators used in music composition, production, and performance—if they choose to do so. This article isn’t about whether people should use AI in music. It’s a free world, and everyone should be able to experiment with new technologies if and as they wish—disclaimer over.

Voice cloning, at its core, involves replicating a person’s voice with a certain level of accuracy using AI-driven algorithms. Through the analysis of audio recordings, AI systems can capture the nuances of a vocalist’s tone, timbre, and vocal characteristics, allowing for the synthesis of entirely new vocal performances that sound indistinguishable, at least to some extent, from the original.

But where there is music, there are copyright concerns. Ensuring that artists’ creative works are protected from unauthorised use or replication has become a priority for most industry players in 2024, major record labels included.

One good example is the “Heart on My Sleeve“, a Drake and The Weeknd deepfake. This AI-generated song caused a huge stir while highlighting the creative potential and ethical debates surrounding voice cloning. Despite being created by a human, the vocals were not legally acquired or cleared by the label or artists; therefore, the song has no commercial value.

Another application of voice cloning in music is preserving and recreating musical legacies. AI-driven voice cloning technology enables artists to recreate the voices of historical figures, iconic vocalists, or deceased musicians, allowing their music to live on in new compositions and performances.

An instance you may be familiar with is the recent Beatles release, in which Peter Jackson employed AI-assisted technology to isolate audio from exchanges that would have otherwise been drowned out in the studio chaos. Today’s technology allowed producers to extract John Lennon’s vocals from an old demo tape and breathe new life into “Now And Then.”

A longstanding fascination with voice cloning and voice recognition

Our fascination with the potential of voice cloning and transformation has spanned nearly 3 decades. In 1997, Yamaha and the MTG initiated their first collaborative research project. Simultaneously, Pedro and Àlex, BMAT founders and until recently CEOs, were fresh graduates from the ETSETB, the Engineering School at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, who joined the MTG team, despite having limited prior achievements or recognition.

Their initial project with the team, known as “Elvis,” aimed to transform users’ voices into those of their idols using Yamaha karaoke machines. Although the project was prototyped, it did not advance beyond that stage. Still, the work laid the groundwork for MTG’s subsequent project with Yamaha, “Daisy.”

Daisy represented a research endeavour focused on developing innovative, high-quality singing synthesis technologies. The project derived its name from the earliest known synthetic singing that we mentioned earlier, IBM 7094 at Bell Labs. Unlike Elvis, Daisy remained within the confines of the research facility. Years later, it evolved into Vocaloid, a singing synthesiser that achieved significant success for Yamaha after the release of virtual singer Hatsune Miku in collaboration with Crypton Future Media.

Warning: this is a very catchy tune. Listen at your own risk.

Can voice cloning be ethical

Voice cloning in music offers vast potential for innovation but also triggers significant ethical concerns and challenges. Issues surrounding copyright, consent, and authenticity emphasise the importance of responsibly developing and regulating this technology.

Moreover, the risk of misuse, including unauthorised impersonation or transformation of vocal performances, underscores the necessity of establishing ethical guidelines and safeguards. These measures are essential to protect artists’ rights and maintain the integrity of musical expression.

The European Union’s recent passage of the Artificial Intelligence Act in March, aimed at regulating AI and safeguarding copyrighted music, raises crucial questions about the ethical implications of voice cloning technology. The act includes multiple obligations for AI companies, including openly declaring their training data set and ensuring that any AI-generated track is clearly identified as such. While the act also mandates transparency around copyrighted materials used in AI training, including music, it highlights the challenges of balancing innovation with protecting artists’ rights and intellectual property.

The push for detailed summaries of copyrighted works and watermarking training datasets shows how the EU is serious about developing AI ethically. But, this law’s global reach, even applying to data collected outside the EU, could make one wonder how effective it’ll be and its impact on the global AI scene. As other nations draft their AI rules, the EU’s method could be a blueprint for handling the tricky ethics of voice cloning and AI-made content. Only time will tell.

Voice-Swap and us

We believe that AI should empower creators and artists while crediting and protecting creators and rights holders.

Our recent collaboration with Voice-Swap, which has given birth to a pioneering certification program to ensure the ethical use of AI in voice cloning and recognition, is a testament to our commitment to revolutionising the AI music landscape.

Through our certification program, we are actively shaping a future where AI and the music industry not only coexist but thrive together. For this to happen, transparency is key.

Our view on copyright considerations when voice-cloning

Nonetheless, it is important to note that Voice-Swap is training voice models. As of now, they are not generating melodies, beats or lyrics, they are converting a voice signal. What they infer from their training data set – i.e. in principle solo voice recording of signed singers improvising – is not a sequence of notes but the choreography of their vocal apparatus. That includes things like where the formants are, how long the pharynx is, how open the mouth is when they transition from “aah” to “eeh”, or how narrow the nasal cavities are.

How does the BMAT AI certification work

AI product developers who seek our certification willingly submit their data to us, where we cross-reference it against our database to verify if copyrighted material has been used during AI training. This process ensures compliance with copyright laws and fosters transparency and trust within the industry.

We’ll showcase how it all comes together with our latest partnership with Voice-Swap.

First, the training data that has been used by Voice-Swap is sent to BMAT’s API for extensive audio fingerprinting analysis. If the analysis detects no copyright infringement, our Music OS sends a “No copyright infringement” message to the Voice-Swap API. If copyright infringement is detected, the OS sends a notification with the title and artist of the infringing music track, allowing Voice-Swap to take appropriate action.

Our lifeblood—the audio fingerprinting technology—is the foundation for producing these results. Audio fingerprinting analysis guarantees that only copyright-free content was used during the training stage. If the training data is copyright-free, we don’t have to worry about the generated AI content, which won’t be similar to anything copyrighted.

After all, the AI only learns what is used during the training phase.

How can our technology help certify AI companies

We leverage our extensive database of 180 million audio fingerprints and highly refined audio tracking technology to meticulously examine and analyse the training data of AI music models.

Over the years, we’ve tested our standard audio fingerprinting solution, a multi-purpose technology, with a wide variety of degradations, such as noise, background music and pitch shifting for the best possible and accurate results.

Our fingerprinting technology first computes a time-frequency-energy representation of the audio, which can be visualised as a monochrome image that carries most information of the original waveform. From this representation of the audio, we then select discriminative robust events that are likely to survive in challenging conditions (e.g. background music).

These events are indexed for later quick search in hundreds of indexes, each made of hundreds of thousands of tracks, distributed in a network of servers (the total sum > 168 million tracks). When an unknown audio is received (e.g., from the training data), the fingerprint of this audio is compared against the premade indexes so that we can find the closest match against all our catalogues very efficiently.

How could other AI companies benefit from it

Our certification program offers massive benefits to both AI companies and product developers, as well as the industry as a whole.

Our open and verifiable audit trail instils unparalleled transparency, demonstrating a commitment to ethical practices that build confidence in users and partners. The AI BMAT certification mark is a symbol of trust, giving certified models a competitive edge in the market. This distinction sets certified products apart and highlights their adherence to responsible AI development.

Our certification may significantly reduce the risk of legal challenges associated with copyright infringement, safeguarding all stakeholders, from developers and users to all members of the music value chain. By ensuring the legality of training data, we help companies avoid financial and ethical disputes and protect users from potential copyright violations.

Our certification also ensures adherence to international industry best practices and standards, paving the way for global expansion. This compliance allows certified products to navigate the complex legal landscape and expand their reach into new markets.

By prioritising rightsholders and artist compensation as well as responsible data sourcing, we can set a new industry benchmark for ethical AI practices. Our certification helps companies prioritise fair compensation for artists and rights holders and source training data responsibly, promoting a more equitable and sustainable AI ecosystem.

Looking AI-head

As AI-driven voice cloning technology continues to evolve and mature, its impact on the industry could grow stronger. As we navigate the opportunities and challenges ahead, responsible development and ethical use of voice cloning technologies will be essential to ensure its positive impact on artists, audiences, and the future of music.

Driving innovation at the intersection of music and technology has been our thing since ‘06, and this certification program for AI training datasets marks a significant milestone in our story—it’s just the beginning of many groundbreaking initiatives we have in store. We’ll tell you more about them as we go.

If you’re an AI company looking for a way to certify your AI models and ensure the integrity and legality of your training sets, get in touch with us to see how our AI music certification program could come into play.

Latest articles

November 19, 2025

Inside BMAT DSP Processing: How SIAE turned operational clarity into stronger licences and faster distributions

Some relationships last because they work, others last because they grow. For more than 10 years, we believe the partnership between SIAE and us has done both. Across products and people, w [...]

October 9, 2025

KODA and BMAT Announce Landmark Global Partnership for Music Rights and Royalties Management

BMAT, a global leader in music technology and rights and royalties data, is proud to announce a new partnership with KODA, the collecting society for songwriters, composers and music publis [...]

March 26, 2025

Inside ReSol: An interview with SACEM on rethinking how digital claiming conflicts are resolved

Much like family gatherings, the intricate world of digital music rights is no stranger to conflict. With frequent occurrences like overlapping ownership claims, metadata inaccuracies, lice [...]